On Reading Stoner as a 2025 Guy

Why do men feel so drawn to reading Stoner in an age where men don't read?

It’s a common situation for any male bookreader who spends time with others like him: You ask your boy if he’s read anything good lately. He gives an emphatic yes, saying he is in the middle of Stoner by John Williams. Your other friend jumps out of his chair, singing its praises while recounting the days-long melancholy he found himself in after finishing it. You, the curious reader, decide to put it on your TBR list, but the FOMO grows stronger as your group chat continues to pop off about it, so you decide to jump in as soon as you can. Despite the emotional wreck the book makes of you, you keep going, because you must find out what William Stoner makes of his life. When you finish, you too find yourself in a days-long bout of melancholy as you take stock of your life, weighing the highs against the lows to see if you’ve found anything remotely close to fulfillment. You text your boys about it— “justice for stoner even though he fucked me up” – and the next time a man of letters asks for book recommendations, you preach the good word and pass it on.

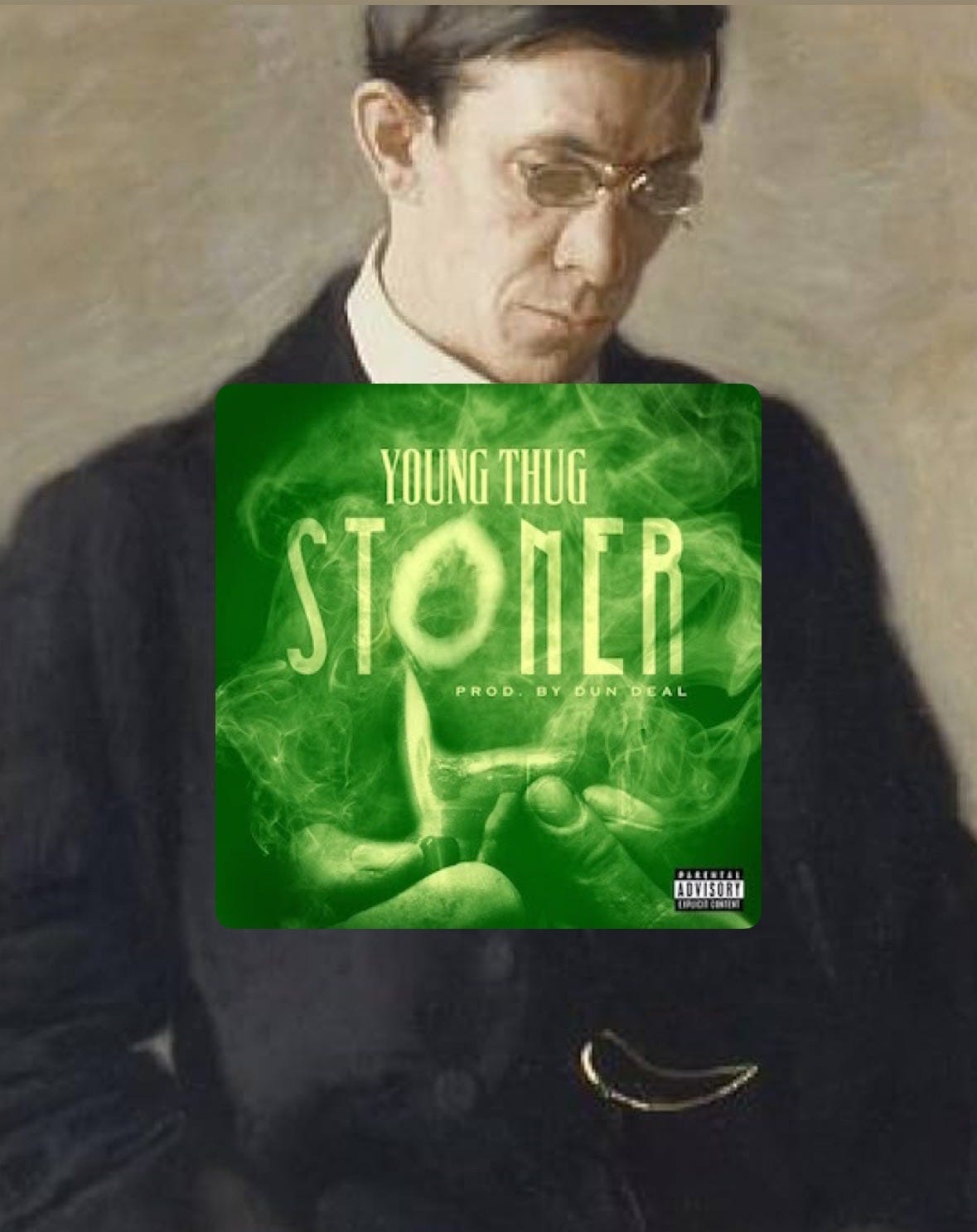

What is it about Stoner that continues to captivate the minds of men around the world? Is part of it the NYRB cover, a portrait by Thomas Eakins of his brother-in-law Louis Kenton, who though stanced up and swagged out, is clearly downtrodden and weighed down by his solitude?1 Is it the title, a single word that evokes images of smoking weed and Young Thug? Perhaps it is actually the text itself, a story told in clear, flourishless prose about the life of William Stoner, a meager farm boy turned English literature academic whose decision to pursue the humanities over the course of his life brings him more pain than joy, and whose death brought no grand processions, his only lasting legacy being a campus tombstone for college students decades down the road to toss their cigarette butts onto after ripping bogies in the cemetery for the vibes.

What does it take to make a man cry? On a recent flight, I got to the point in Interstellar when Matthew McConaughey must watch 23 years of video messages from his children despite only experiencing an hour or so of time himself, witnessing his teenage son grow up, get married, birth a child, and lose a child in the span of minutes. I had to hold back tears because I wasn’t going to leave the cabin in shambles. The textbook example of this phenomenon, I swear, is Click, the Adam Sandler movie featuring fatsuits and a time-manipulating remote. Despite experiencing very little of life at ten years old, I couldn’t help but sob as Adam Sandler fast-forwarded through his own, missing personal milestones and important moments with his family so he can skip to the moment in his career when he’s finally successful. To watch someone so doggedly pursue what they believe is their purpose, to the exclusion of what truly makes life worth living—this breeds a fear of wasting one’s own life.

Some of the same principles apply, oddly enough, to John William’s Stoner. The passive way Stoner experiences time can throw readers into a depression, leaving them to wonder if they too just coast through life. He numbs himself with the routine of his work, and in his later years, after much of what he loved has been taken from him, he grows mindless and cranky, indifferent even to the sources of his torment, spending more time in the home he shares with his wife who has spent years making his life hell. The portrait of Stoner at old age inspires pity for him and fear for ourselves that we might end up like him if we continue to let life happen to us without wresting control of it.

For some reason, Stoner has a reputation amongst the chronically online, despite having nothing to do with the internet or the perils of mass media that could’ve been addressed at the time of its publishing in 1965. Ever since the republication of Stoner in the 2000s by NYRB Classics, there’s been a renewed interest in the book, and since then scores of men have discovered the novel for the first time. Because it hasn’t received the David Foster Wallace red flag treatment yet, one feels unashamed to read it freely in public and private, and to discuss it at length wherever they may choose, on Twitter, Reddit threads, or in person with the boys. In the way that everyone always seems to be reading Mating, the fellas are always getting into Stoner2.

The question that animates much of the discourse around the novel and likely haunts the minds of its readers in a not-so-subtle act of projection is whether Stoner lived a good life. Given the sum of his regrets, miseries, passivities, joys, ecstasies, and revelations, it’s a fair question without an obvious answer. After all, his decision to pursue his love of letters haunts him in many ways. He abandons his parents and discovers their passing via phone call, burying them alone on the land on which they raised him. He forgoes military service to study at university, and the death of a close friend in his cohort who fought in the war weighs heavy on his mind as the years go on. His unhappy wife, Edith, becomes the source of an unhappy life, as she wages psychological warfare in their home and finds sly ways to cut off his relationship with his daughter. The list goes on, and Stoner cannot catch a break anywhere. Whenever he begins to establish a comforting rhythm of life, new challenges arise. Even his desire to teach and live a life of resolute mediocrity at the university is thwarted by the arrival of a combative department head, and his love affair with a younger instructor is cut short by petty university politics. He is always going through it, and in his final moments, though he manages to find peace, we are reminded of how this book began:

“... his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past and no identity with which they can associate themselves or their careers.”

In his intro to the New York Review of Books re-issue of the novel, John McGahern quotes John Williams in an interview with Brian Woolley, claiming that Stoner is a “real hero”:

“He had a better life than most people do, certainly. He was doing what he wanted to do, he had some feeling for what he was doing, he had some sense of the importance of the job he was doing… The important thing in the novel to me is Stoner’s sense of a job. Teaching to him is a job – a job in the good and honorable sense of the word. His job gave him a particular kind of identity and made him what he was… It’s the love of the thing that’s essential.”

This interpretation is the one that frames the novel as something like a homily. It is an antidote to the Alpha Male and Great Man™ propaganda we are fed by popular media, where our heroes save worlds, start companies, run countries, and optimize their lives to maximize profits and muscle gains. This contemporary strain of male optimization philosophy – “founder mode”, “grindset”, “the great lock-in of Sept/Dec” – encourages its participants to spend all of their waking time in pursuit of advancement. Everything must be productive, and even if you have time to read, you should be reading Atomic Habits instead of some brooding, melancholic work about a guy who doesn’t do a whole lot.

When we read Stoner we encounter a protagonist whose principles align more with those of a man who would dare read literary fiction in 2025 than someone interested in securing VC funding for some agentic AI platform that will constantly run simulations based on the data of your life to chart you the best course of action to reach enlightenment. The former is a believer in prose that’s psychologically probing and ambiguous in its moral lesson, and chooses to engage with such a pastime even if it delays or impedes material advancement, which we’ve been conditioned to prize as the ultimate expression of manhood.

Part of the appeal of William Stoner is that he exists somewhere in between the extremes of male literary protagonists out there. He is not the freak of a Tao Lin novel (which is just some barely fictionalized version of Tao Lin himself if we’re being precise), nor is he the archetype of white male rage that our culture has been obsessed with dissecting for years now. Though he is committed to his work and finds spiritual nourishment through it, he isn’t particularly special or gifted in some aggrandizing way that distinguishes him from us commoners. I asked the homie Brian, who gave a glowing recommendation of Stoner on his excellent podcast Middlebrow, why he thought he and other guys felt so drawn to the novel:

“I love Stoner for its deeply empathetic portrayal of ordinary life, and the rich inner worlds that we all possess, but rarely reveal. Not to get all ‘male loneliness epidemic’ about it, but I think men who were raised in a more emotionally closed off environment can relate to the way Stoner navigates profound life experiences in complete isolation.”

It would be easy in a cynical age to dismiss this as sad boy literature, to add an identification with William Stoner’s frustrated pursuit of happiness to the growing list of “performative male” signifiers. But shouldn’t a person who tries to find the good in life be deserving of our admiration instead of our mockery?

In the hands of a lesser novelist, Stoner’s life would be bursting with histrionics: screaming matches with his wife, a climactic showdown with department head Hollis Lomax – hell, if a certain celebrity writer went “Vuong-Mode” with this story we might’ve gotten a page-long passage about the way Stoner’s hands felt the last time he embraced Katherine Driscoll, something about her dead skin cells burrowed into his palms, the memories imbued therein connecting them forever. Instead, Williams opts for a plain style of writing to match the plain life of his protagonist, and this clear prose allows for some profound meditations when directed towards describing the truths Stoner uncovers about life and love. That Williams is able to stir up such intense emotions despite the lack of overt drama is what allows us to easily map Stoner’s life onto our own. Sure, he might’ve lived a minor life, but how many of us do?

Perhaps Stoner resonates with literary men today because of their own perceived obsolescence in a world where men “do not read fiction”. How true this is doesn’t matter to me, but I’ll wager that the average reader of Stoner sees enough of this schlock about the “the crisis of literary men” floating around in purported publications of note that they consider themselves an aberration in modern culture. Like Stoner, who opted for the rhythms of Medieval poetry over trench warfare, today’s male readers might feel their pursuit of an aesthetic life has sidelined them from the more momentous endeavors of the day (like, genuinely, AI expansion). Of course there are AI tech lords who are also readers out there, but the guys I have in mind might work middling jobs in or adjacent to media or publishing that they’re overeducated and undercompensated for. They eat shit from their boss and say nothing, retreating into a world of letters where the text cannot abuse you, even if it can hurt you. William Stoner lived a life of regrets and agonies, and though we fear we will do the same if we chart his spiritual course, we find that he discovered true love in his work and his affair with Katherine Driscoll. Though these things were imperfect, and at times painful to work through, he got a taste of the good stuff, and by the end, what else did he need?

The average male reader of Stoner does not across it on a generic list of the “100 Greatest Novels of All Time”, alongside Crime and Punishment and Gravity’s Rainbow. It is fair to assume they might be more sensitive than the average guy, given they feel compelled to read a book whose casual pitch is “it’s really sad, nothing really happens, but it’s really really powerful.” Ultimately, upon finishing it, they find that is an affirmation of their own life choices, validating their wavering belief that to pursue something that is under the constant threat of irrelevance can actually give us everything we need.

A few days ago, I went to the Met to look at the Thomas Eakins portrait, in the hopes that staring at it in person will reveal something to me about the significance of the novel and its impact on me. I’m a sucker for these kinds of pilgrimages, though historically they’ve given me no answers. I braved a torrential downpour in nice linen pants and walked around the American Wing with my eyes peeled until I stumbled upon it in the corner of a room full of towering portraits by John Singer Sargent. It was the only one without a gilded frame, and the only one of somebody not of some distinguished status. Seeking revelation, I spent several minutes staring in silence, but nothing came to me. After checking out some Winslow Homer paintings, I returned and found a tour guide explaining the backstory of the Sargent portraits. I loitered in the back, hoping he would eventually say something about the inspiration behind the Eakins painting. After several minutes, he declared that they were running out of time, and so they shuffled out of the gallery, right past Louis Kenton. I walked back to the image. From my vantage, he looked larger than life and around seven feet tall, though given the actual dimensions of the painting, he was probably closer to a common six feet.

In Darell Sewell’s book on the works of Thomas Eakins, Kenton is described as someone who always aspired to “white-collar status”, the son of a flour and grain salesman who became a bookkeeper. Very little was known about him besides his violent and turbulent marriage to Eakins’ sister-in-law Elizabeth MacDowell, though he is the only person not of some prominence that Eakins has painted. Sewell asserts that:

“Kenton’s vague identity forms the basis for the ultimate naturalist challenge: a picture without narrative, setting, distinctive costume or properties, dramatic “gesture or attitude,” yet richly signifying the character of modern life and art. His relaxed posture, thoughtful expression, and baggy dress suit must convey all we can know about his world.“

There are Stoners everywhere for those with eyes to see… shoutout to the folks at NYRB Classics for picking a cover that is in direct conversation with the text inside instead of some overstimulating rainbow slop designed to catch the eyes of some ADHD screen demons.

Beware, dear reader, for our time is short. They are concocting new bros by the day. The literary Brodernist, the Bolaño Bro, the Knight of Knausgåard… soon enough you will question your tastes after watching a Tiktok captioned “run away if he has THESE books on his shelf,” and find Stoner sandwiched between Infinite Jest and that Rick Rubin hardcover manual for aspiring vibelords. Suckers for Stoner.

What a tremendous review of an incredible book. I really love the way you ended it.

To me this book is in many ways, the pitfalls of trying to live a principled life. He does not leave his wife, does not admit Walker because he has such unwavering faith in what he believes to be right and good in the world. As Masters tells him, Stoner sees the university as a repository of the “the True, the Good, the Beautiful”.

Williams shows us so plainly that good deeds may not result in good outcomes, but does so without any prescription for the kinds of lives we should live.

Enjoyed this read! Guys like this book because they can relate to a bookish guy who lives an okay though disappointing life, gets into a bad relationship with a woman, and deals with it all in a non-crazy way.