on catholicism and a spiritual Life

stray, raw, and oftentimes contradictory, like many of life's mysteries

In the months between graduating college and finding my own place, against my wishes, Sundays were between me and God. I was jobless and living with my parents’, which meant playing by their rules, which meant waking up with a rocking hang over at seven-thirty to get ready for Mass at eight-thirty at Mary’s Nativity, my childhood parish. I’d throw on last night’s shirt if it had a collar, and I’d stumble into the backseat of the car begging for a moment to breathe. My breath always reeked of Saturday’s cigarettes, but the church’s incense was stronger. As Mass began, the throbbing in my head drowned out the organ and the priests’ words. The only way I could tell how far along we were in the Mass was by the number of times we had stood up and sat back down. We had gotten up for about the fifth time, which meant a Gospel reading followed by a homily. As the congregation took their seats, I’d wiggle past my father out of the pew and walk leisurely to the bathroom, where I’d sit on the entirety of the homily. And every single time, I returned right as it wrapped.

For many of us lapsed Catholics, there isn’t a moment of formal denouncement. I’d wager it’s more of a drift from than a sudden loss of faith. In Catholic high school, my buddies and I would hear things in Theology class, about creation and abortion, and tell ourselves that this can’t be right, and that we’d rather not live like this if we didn’t have to. We were tested on the meanings behind the words we had said so blithely during Mass, and we were expected to believe in things like transubstantiation, knowing it was silly to believe bread was body, port wine was blood. And yet, we continued along with these rituals, reciting the words and performing the sacraments, praying that the communion wafer would hold us down until lunchtime. It didn’t take too much out of us to do these things, and it kept the peace then just as it does now when I attend mass with my parents. I don’t not believe in God so much as to stand in protest, and I’m too old to be rebelling against my parents. It’s easier to be a lazy Catholic than a devout atheist.

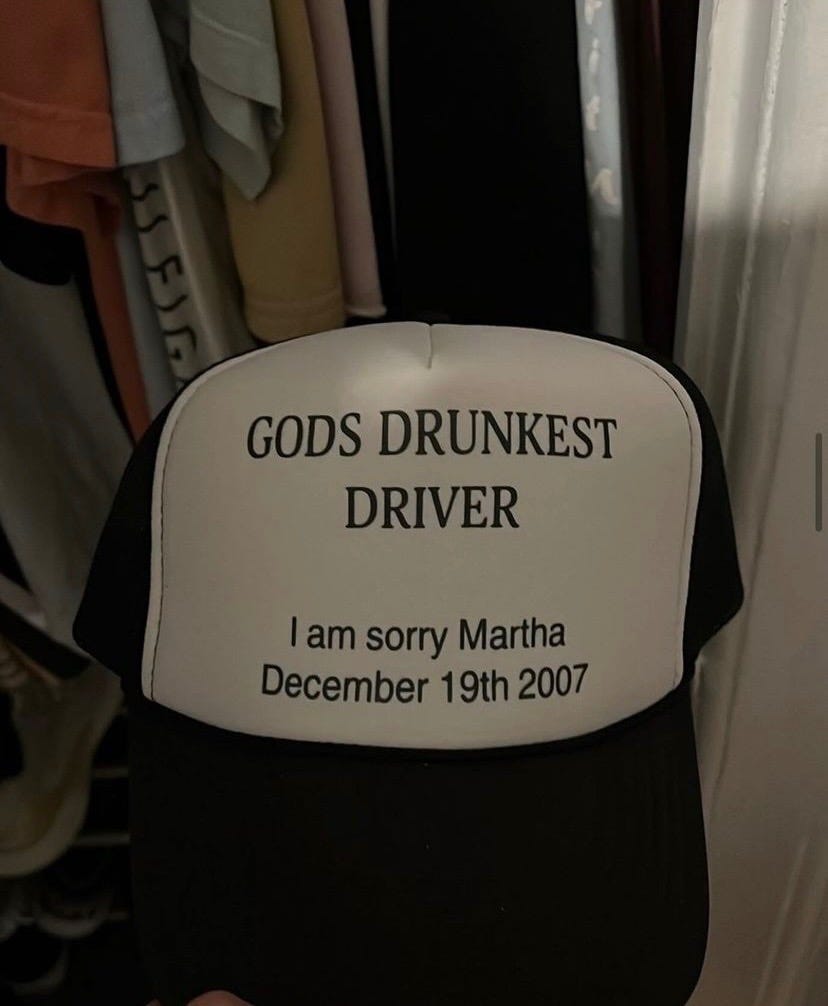

These days, I’m in a murky situationship with Catholicism. When I tell people I went to an all-boys Catholic high school with mandatory Theology classes and religious retreats, they often ask me if I’m religious, or if I still believe in “all that”. I’ll dismissively say no, because I don’t want to look like a freak. But the answer is far more complicated than that, not because I do believe, but because I’m not sure if I ever did. Very rarely did I ever live in fear of God’s wrath or judgment, having lived a life of moderate vice. I didn’t fully buy what they were teaching me, but part of a younger me wanted to believe there was a God who saw all of this and thought it was a little ridiculous, that we were so concerned with ritual it obfuscated what mattered: living a moral and ethical life. I created an image of God palatable to my circumstances. In my mind, he thought it was chill that I ate meat on Fridays, lied to the priest during confession sessions, and took shits during homilies. My God thought that saying Ten Hail Marys wouldn’t absolve me of anything, but making it to mass on Sunday with a hangover and cotton mouth from Marlboros made me a good person.

I sometimes have a Pavlovian response to Catholicism in the wild. It happens most when I visit churches in other countries. They’re often gorgeous, and upon entering I find myself in awe of this intersection of fanaticism and extravagance. Everything is expensive and gold, and beautiful frescoes adorn the ceilings above the altar. If I’m there alone, I’ll sit in the pews in silence, or kneel and strike up a conversation with God, beginning every session with “it’s been a while.” If mass is in session, despite the language barrier, all I have to do is count the number of times we’ve stood and sat for a sense of how far along we are. If it’s not, I’ll get my fix of piety by looking up the history of the saint associated with the building, maybe even recite a prayer if they have one. I’ll pay Euros or Pesos to light a candle for whoever is in my life. I find myself doing things I would be never caught doing in America. Whenever these church visits happen with non-catholic friends, sure, we sit and marvel at the art and architecture, but I can’t know for certain that there is a spiritual element to their awe. We’re all visitors, but I’ve been in this house a million times. I genuflect when entering a pew or crossing the altar. I relay the history of each Station of the Cross. I know when to get out to make sure we don’t get stuck in an hourlong service and miss our dinner plans. It’s one thing to uncover these histories on your own as an intellectual and artistic fascination, and quite another to remember learning these stories through Veggie Tales videos in grade school.

****

Among a certain class there exists a disdain for those who even slightly believe in a Christian God. Hell, I even think it’s weird sometimes, but I’m trying to come around on the whole thing. Who are you hurting by giving up an hour of your week to something other than yourself? To be in community in a world where doing so has become increasingly rare? To criticize an institution for its corruption and for enabling a system of widespread sexual abuse is valid and even encouraged; thinking of yourself as superior to someone else because you think their beliefs are stupid is something else entirely. To assume that anyone who is religious has an uncomplicated relationship with their faith is narcissistic behavior, and to believe you are better than them for believing in nothing but your phone and the ground beneath you doesn’t make you a scholar of reason – it makes you an asshole. In a world filled with suffering, is it crazy to look for an instruction manual on how we can make it better?

On the flip side, I noticed Catholicism becoming trendy a few years ago, mainly online and by those who spend too much time online, among a cohort I once believed to be godless. People mixing their rosary beads with their realtree prints and Margiela, deep fried photos of people in prayer pose with hands folded worshipping the slab of stone at teh center of Dimes Square, Jesus incorporated into the meme iconography of the day. There were more fanatic iterations of this, from “hot mass” in the city to Red Scare listeners preaching tradcath philosophies. Most of them were white, and, if I had to guess, did not grow up in the trenches of the Church. They somehow thought they’d appear transgressive by adopting the sensibilities of one of the most powerful and influential institutions in the world.

It was strange to see my spiritual upbringing refracted by such bitter white-person irony. I couldn’t tell if they actually believed in it all or if it was just cosplay, or if their relationship to it was just as complicated as mine. (If I had to guess, it was just another performance of identity, which has been the dominant form of expression in downtown New York over the past few years, where performing a certain self online and offline trumps any production of actual art.) Initially, I believed the aestheticization of Catholicism hollowed out the spiritual experience, and found myself humming something along the lines of “my culture is not your costume.” But wasn’t it a costume for us too? In middle school, kids often wore rosary beads as a fashion statement. They flexed their golden communion bracelets and mini Jesus pieces, and posted bible passages on Facebook and Instagram to function as motivational quotes. At the very least, we suffered through it as children, which gives us permission to do whatever the hell we want with it as adults.

****

I’m always struggling to maintain a semblance of spirituality in my life. I hadn’t been a staunch believer of Catholic doctrine for quite some time, but I always considered myself a spiritual person until recently. Mostly, that meant breathing every once in a while, being mindful, interrogating my intentions, and allowing myself to be captivated by the beauty of the world. For a while, I retreated deep into myself, obsessing over imperfections and insecurities until I believed that my inadequate life was completely of my own doing. I spent thousands of dollars in therapy trying to figure out what was wrong with me, and told myself if I fixed this fatal flaw, or that fatal flaw, everything would fall into place. I began reckoning with the possibility of a pathetic life, that this was just my narrative arc, that I was born with bad luck and a bad attitude. Then, along the way, something shifted. There wasn’t a moment I can point to as the start of my journey back toward a spiritual life. But at some point I stopped looking inward so much and started to submit to the symmetry between the mysterious workings of the world and the mysterious workings of myself. Instead of thinking too much about why I am the way I am, I developed a fascination with what was right in front of my face. This included witnessing everything from springtime flora and cherry blossoms to moments of kindness between strangers, to conversations with friends and others whose lives and philosophies were vastly different from mine. In getting out of my head, I came to appreciate that something else was at play, something beyond my control, and that part of finding peace was making peace with this force, moving in tandem with it, while still maintaining the freedom to question it when something doesn’t seem right. Call it coincidence, faith, the alignment of the stars; call it God.

In some ways, I miss the clean-cut, Catholic life. While it was hard to abide by its many rules, at least you knew you were working towards something — salvation after death. It’s kind of like school: you pass the test and get good grades, you make it to heaven. These days I live in doubt about what this all leads to. Do the bad rot in hell? Do the good rest in peace? I’m afraid of committing to the idea that nothing waits for me after this, but I try my best to be good in the meantime.